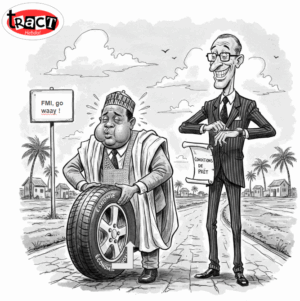

[L'ET DIT TÔT] Sénégal : le FMI, ce banquier qui nous veut du bien… ou pas ? (Par Ousseynou Nar Gueye)

The Sonko 2 government tells us we can live without the IMF. It's like saying we can live without oxygen: it's possible, but not for very long. They talk to us about "budgetary sovereignty" while simultaneously checking if our Ivorian neighbor has 100,000 francs to lend. The promised economic clarity increasingly resembles a January fog in Saint-Louis on the eastern waterfront, behind the presidential palace on Avenue Léopold Sédar Senghor. For the past few weeks, the hushed corridors of the Senegalese administration have been echoing with a strange melody. A melody of defiance, of newfound independence, a bit like a teenager loudly proclaiming that he no longer needs his parents' pocket money. The refrain? "Senegal can live without the IMF." For us, the idea of economic sovereignty is a sweet dream we cherish fervently. But we tell ourselves that autonomy is good, but self-sufficiency is the shortest path to peanuts and bread and candles for light.

The government assures us that the country is on the right track, that of "fiscal sovereignty." Gone are the dictates of the Bretton Woods institutions, those distant bankers who tell us how to manage our money, as if we were unruly students and not a sovereign and responsible nation. On paper, it's magnificent. We can already imagine budgets passed to the rhythm of the sabar drum, spending that meets the real needs of the population without passing through the puritanical filter of "structural reforms" and "necessary adjustments" that always end up hitting the most vulnerable.

But between the impassioned rhetoric and the reality of the state coffers, there's an ocean of questions. To say that we can live without the IMF is a bit like declaring that we can live without oxygen. Theoretically, it's possible; we can hold our breath for a while. But reality quickly catches up with us, and our faces turn a rather… gray. Senegal, like many developing countries, has a long-standing relationship with the IMF, a relationship that is sometimes tumultuous, often forced, but always there, like that slightly overbearing old aunt who lends you money but feels entitled to comment on your diet.

Historically, the IMF is more than just a lender. It's a label, a stamp of "good conduct" for international financial markets. When the IMF supports you, private investors look at you more favorably, and interest rates are less exorbitant. Doing without it means risking being alone in the market, begging for loans on far less favorable terms. That's where the "neighbor with $100,000 to lend" becomes truly meaningful. Because, in economics as in life, when you proclaim your independence, you first make sure you have the means to finance it.

"Inflating this tire is hard, eh…!"

"Inflating this tire is hard, eh…!"

The government, in its infinite wisdom, promised us "economic clarification." We were expecting a detailed roadmap, with figures, projections, and contingency plans. Instead, we got a London fog hanging over the Corniche. A thick mist where speeches get lost, figures contradict each other, and where we end up no longer knowing whether we're moving forward or backward.

We hear talk of "internal resources," "spending control," and "project prioritization." These are all noble concepts, but their concrete application remains unclear. How will we fill the deficit if the IMF is no longer there to provide support? What new "sovereign" sources of revenue will replace the billions that the Senegalese welfare state costs us? Will oil and gas, whose exploitation has yet to make us rich, magically appear and save us? Or will we invent a tax on selfies or Facebook "likes"? On the left, there are calls for transparency; on the right, there are concerns about the consequences of these announcements.

The idea of "going on a diet" without the IMF is appealing. It's like promising to lose 10 kilos without changing your eating habits, just by repeating "I'm thin" in front of the mirror. The reality is that "going on a diet" means making painful choices: reducing public spending (which often means fewer subsidies, fewer public sector jobs, less social investment), optimizing tax collection (which never pleases anyone), and diversifying the economy (a major challenge that takes years).

The IMF, despite its flaws and reputation as a "bad banker," is also a mirror. It reflects back to us our imbalances and inefficiencies. To do without it is to refuse to look at that mirror, at the risk of repeating the same mistakes, but this time without a safety net. And for a country with development ambitions and a young, demanding population, that's a risky gamble.

Ultimately, who will pay the price for this self-proclaimed "budgetary sovereignty"? The people, of course. If the state coffers are emptied, it is public services that will suffer: healthcare, education, infrastructure. Youth employment will become even more precarious, and purchasing power will erode. On the left, we have no interest in political ego battles; what matters to us is the well-being of the people. And if this professed independence translates into a tightening of the belt for households, then it will be a bitter pill to swallow.

Senegal's economic history is littered with IMF programs, failed reforms, and broken promises. Perhaps this time, the government has a brilliant plan, a magic wand that will free us from constraints without suffering the consequences. But we've learned to be wary. When a politician talks about independence without providing the means, we tend to check if our pockets are still full.

The IMF is a crutch. A crutch that is sometimes painful, forcing you to walk a certain way. But without it, you risk falling. The Senegalese government tells us it can run without a crutch. We'll believe it when we see it. In the meantime, all eyes are on the announcements, the figures, and above all, on the daily lives of Senegalese people. Because "fiscal sovereignty" is only worthwhile if it translates into a concrete improvement in the living conditions of the population.

Or will Senegal, in its quest for independence, simply replace its crutch with a walking stick, seeking other lenders, perhaps less scrupulous about governance, but just as voracious when it comes to interest rates? Time will tell. But one thing is certain: we will continue to observe with our critical left eye and strike with our impertinent right, so that the fog on the coastline dissipates and economic truth finally illuminates Senegal's path.

P.S.: It is important for me to emphasize that I support this 'Diomayat', the political regime of the duo President Diomaye and Prime Minister Sonko. This opinion piece is therefore written in the name of the principle that 'spare the rod and spoil the child'. A word to the wise.

Serigne Dawakh, Ousseynou Nar Gueye.

Founder of Tract Hebdo ( www.tract.sn ) ; President of the civic and citizen engagement movement '' Option Nouvelles Générations – Woorna Niu Dokhal''

Commentaires (5)

Participer à la Discussion

Règles de la communauté :

💡 Astuce : Utilisez des emojis depuis votre téléphone ou le module emoji ci-dessous. Cliquez sur GIF pour ajouter un GIF animé. Collez un lien X/Twitter, TikTok ou Instagram pour l'afficher automatiquement.